Download:

Vision Mission

Didjeridu solo by James Barrett

In

1995 I was living in Sydney, Australia in a suburb which was home to

many Aborigines, the indigenous people of Australia. Called Redfern, it

was centered on an area known as “The Block”, a crowded jumble of houses

and old factories where around 1000 Aboriginal people lived on land

that was returned to them by the Australian Government in 1973. Despite

having grown up in Australia this was, at the age of 26, my first

exposure to large-scale Aboriginal culture.

All up I lived in

Redfern about 3 years between 1995-99. The atmosphere changed a lot in

that time. This is a short account of a cultural sanctuary that existed

along side and because of the independant nature of The Block (long may

it live...) [Names changed to protect the innocent.]

The Fern

(1995-96).

Our house looked like a wooden ship long run aground. The

lower decks silted up and stuck fast in the earth. A crew of tattooed

white nomads of soul had moved in. Hair every color of the rainbow,

fleshy bits pierced, and always curious to pick through any unattended

pile; rubbish or recycle, silo or asylum. We would occasionally awake to

find strangers sleeping in the basement cellar spaces. These homeless

or traveling folk would usually be given tea and porridge before they

jumped back over the fence into the world beyond. Once a wine merchants

premises, three huge brick barrels like rooms made up the ground floor,

and each opened out onto the tiny backyard which was being composted

from day one; vegetables drawn from cement. The middle and main story

was four large rooms with a verandah running along three. Sculptures of

twisted metal, bone, plastic, feathers, artificial limbs, manikin

torsos, crazy flags, and banners hung from the railing and tumbled down

into the garden where a two meter dragon with leather wings and a

rotating blades for a head presided over a collection of urban jungle

and classical forms. In the rooms above lived a various individuals over

time, but that was usually the first thing they forgot.

I

came to live in Redfern, inner city Sydney, one day, some day; I can't

remember the first day. I remember I was frightened by it long before I

ever saw it. That same thing (brainwashing?) you laugh at today when you

tell people your suburb, and they go quiet and then ask "Is it

dangerous"?

Answer: "I like it because the hype keeps the tourists,

fashion clowns, and yuppies away". The thing I really liked about it the

most was the feel of community, the spirit of the suburb, which spread

an almost equally in distance from the railway station for all

directions but west. Opposite the station beat the real heart of

Redfern; The Block, for this was Aboriginal land. Australia

has existed for only a short time. Before white people named and

claimed, tied her up and robbed her, she was a living, breathing entity.

The spirit of the Aboriginal people is not dead and life in Redfern was

evident of this. This was one step out of Babylon, community where

people don't pretend to be nice, either they are or you know about it

fast. Sure, there was a lot of drugs, and a bit of violence, but we

lived in a state of psychological siege with the TV. telling you what

you've got to believe. As always the thing that everybody wants is

plastic and covered in fingers, and the only way you can be a man is if

you buy a house and have a retirement plan. Fuck the Brady Bunch family

values.

So let me tell you some things of The Fern. Our

house was found by Burn whilst looking at a possible squat site across

the road. It was a tumbled down triple story plaster and timber terrace

with a secret garden in the middle of the city for rent. It was taken

immediately as the deficit was growing for low cost accommodation and

production space for artists in inner city Sydney. A month before ten

years of tradition had ended with the eviction and demolition of 134

Campbell Street, Darlinghurst. This had been a madhouse of creativity

and alternative culture with strong links to the National Art School

just across Taylor Square. The so-called gentrification of Darlinghurst

was ploughing ahead. The way The Glebe and Balmain had gone in the

1970's and early 1980's was happening to Darlinghurst, Newtown, and

Chippendale in the 1990's. At this same time Cyberspace Studios in

Glebe, home at one stage to 80 artists was going through the eviction

process. For a while in 1994 it seemed that everyone who was not

prepared to prescribe to the normality of experts in Central Sydney was

retreating to Redfern.

In Regent Street was to be found

The Golden Ox, once a restaurant, now a venue for everything from Koori

bands to trance traveler's techno parties. It was also home to many,

some long, some short term. In the next block Renwick Street provided

the public with Airspace Studios, Sylvester Studios, and The Punos

Warehouse. A combined living space for as many as 50 artists this was

also perhaps the busiest street in Redfern. Airspace contained a large

warehouse style gallery with different exhibitions and performances

every month. It was managed by one who went by the name of P.C.D-23, a

long time resident of Cyberspace Studios in Glebe. Both Airspace and

Sylvester Studios were situated in a former meat works factory providing

vast combined living and studio space for artists, and both were always

full to capacity during their relatively long history. The Punos

Warehouse was home to the Punos design team who constructed environments

for techno parties, and the interior of their warehouse was testament

to their abilities. A huge dragon and a fly at the entrance leading to a

space filled with all manner of objects floating and flying. Punos

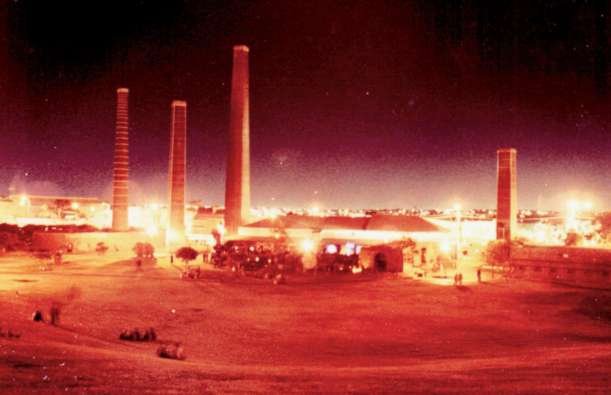

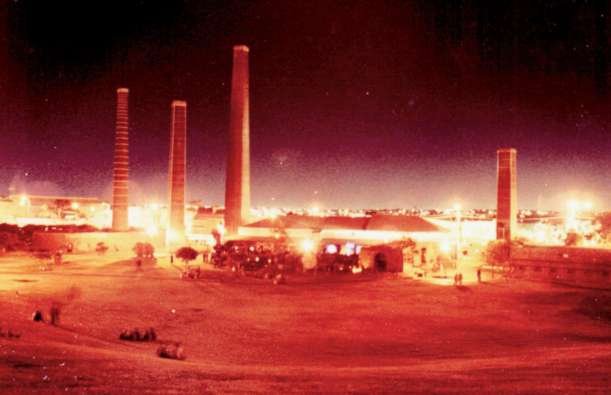

worked a lot with the famous Vibe Tribe sound system in 1993-95, which

ended a glorious career in a police provoked riot with a party at the

Sydney Park brick kilns on 8th April 1995.

Vibe Tribe party, Sydney Park Brick Kilns 1995.

At the city end of Renwick Street on the intersection of

Regent and Cleveland Streets was the Artspace Gallery and performance

space. Not to be confused with the recently government conspired

Artspace in Wooloomaloo, which was created from the building occupied by

The Gunnery, Sydney's most famous artist run space. Around the corner

was 2 George Street, a 6-floor terrace house occupied by many of the

Vibe Tribe organizers (situated next door to the Independent Commission

Against Corruption and as a result under 24 hour video surveillance). It

was at one time the home of 30 adults, several dogs and a few children.

Across the park from George Street, following the eviction of Glebe's

Cyberspace, was the 5 floors of The Sydney Sculpture Studios. About 40

people lived in the warehouse building, engaging in activities ranging

from music to sculpture, dealing and party planning. Next door to the

sculpture studios was one of the few squats in Redfern, occupied by

about 10 punks they made use of the facilities at the Studios for water,

eating, and toilets. At the other end of the street at 186 George

Street were a crowded terrace house and the city base for many techno

style travelers, with around 40 of them crowded into the three floors

for weeks at a time. Around the corner on Redfern Street could be found

140a Redfern Street, a large warehouse space and home to many over

almost 15 years. Heading east down Redfern Street brings one to 120a

Redfern Street, my address and a somewhat typical home for about 30

travelers and wise fools from 1994-98. Some of us worked a little bit.

In fact at most times the house (3-8 occupants at any one time) was

funded by Roy Morgan Market Research (to this day I hate telephones),

and the Department of Social Security (bless the memory). Everyone

wanted to spend as much time dreaming as possible, and did not worry too

much about money. We were living on the almost dead, kissing the

carcass, and taking from the old what we needed to build our own fragile

reality. Somehow it suited the time and the place. This rekindled

philosophy of the hippy aesthetic given a punk attitude. Often labeled

as Ferals it was more than just a fashion for many who embraced this

understanding. Lacking the nihilism of the European so called New Age

Travelers ("Not in this age, not in any age", said John Major), much

angrier than the hippies ever were, and determined to breed and build a

micro-society, unlike the short lived, do or die punk movement. Excess

was the enemy and transcendence was the goal of many. However, as always

with humans the ideal often falls short in practice, and the pressures

against any self-directed autonomous zone are many.

The

top level of our house was a single grand bedroom with cracked plaster

ceiling, two arched windows in each opposite facing walls, a fireplace

at one end. It was like living in a tower. When I came to the house the

tower was occupied by Sev, who began his day much later than most

usually in the area of high noon or sunset. Sev's public life consisted

of, among other things, the Erotometre. A device comprising voltammeter

and frequency generator, with a needle through the penis of each male

(Sev and friend), they became a naked switch in a high pitch electrical

storm of tongues and fingers, touching and rubbing. Sev also performed

telephone research at The Morgue (Roy Morgan Research) but said it was

far below his intelligence (this was true of everyone working there

except perhaps administration). Below Sev's chamber was the velvet cave

of Burn, a witch and sorceress of the highest spirit. It was she,

Burn-Ya-Debts who found the house along with Kira, and the famous

Lebanese/Australian wild poet of the Snowy Mountains, Riesh. When this

story began Burn made statues and told stories. She was drawing and

painting, a poet and student at the National Art School.

The kitchen was the heart of the house. A large round table, dozens of

flowers in dried arrangements hung from the ceiling. Stove was quick to

cook with cupboards full of spice and fruit, vegetables, and soy

products (god bless the bean). Many chairs, a stereophonic

cassette-playing machine, and chai made to order. Famous for it's wall

of obituaries including Andy Warhol, Vincent Price, Sterling Morrison,

Brett Whitley, Tracy Pew, Kurt Cobain, Nico, Frank Zappa, Salvador Dali,

River Phoenix, Kurt Wolf, and more always to come. From the kitchen a

long hall went passed a bathroom with some tales to tell, and many

seashells scattered. Then a small painting studio occupied by the

occupier of the room at the end of the hall. Kira was in love at this

time and shared her room of ancient objects and beautiful cloth with an

intense young artist by the name of Dun. Together they danced love for a

time, made art in every movement, took to walking in parks, making

forward in each other's eyes. This was that moment you find your whole

life out in front of you.

In 1995 the National Art School

was in threat of "rationalization" by faceless bureaucrats unless the

staff, students, and friends of the school could influence the decision

makers. We in our corner of the urban sprawl decided to assist and at a

rally in Martin Place we performed on the back of a Dodge flatbed truck.

So was born Senselesss, a floating collection of performers, artists,

musicians, poets, and attention seekers. Fueled by belief in

existential coincidence, redundant technology, and cannabis, Senselesss

would undertake a variety of acts and demonstrations in numerous

settings over an eventful twelve months.

Sound sculpture

and the collective subconscious were the seeds of the group consisting

of a core of three people and involving many. The large steel sculptures

included a 50 strings box harp suspended from the ceiling, the size of a

coffee table and weighing about 120 kg. Also three round steel bells a

meter in diameter and weighing 100kg each, and a single string upright

base that sounded like a compressor pedal from hell. Combined with

films, tape loops, poetry, lighting effects, fire, costumes, dance, and a

sense of ritual. A variety of reactions were received when we committed

an act. Performances were made at the Sydney College of Fine Arts,

Sydney College of Art, The Metro Theatre, Airspace Gallery, King

George's Hall in Newtown, and for the art terrorist organization

Brainwash. Throughout 1995 there were 12 public performances made and in

1996 the group began to engage in a more private exploration of sound.

Following the suicide of one of the major contributors in early 1997 the

original group disbanded.

By 1997 things in Redfern were

beginning to noticeable change as well. A deal had been done between a

few powerful government appointed individuals in the Aboriginal

community and the South Sydney City Council. The aim seemed to disband

and scatter the residents of The Block (Divide and conquer served the

British invaders well and is still employed in black-white relations in

Australia), and then reclaim the real estate. The heavy police presence

in Redfern was also beginning to give the area a feeling of siege or

open warfare. The harassment and strong-arm tactics from law enforcement

included ten police marching up and down Everleigh Street (the main

street of The Block) in full riot gear and then getting back in the van

and driving away, daily for about two weeks. Street strip searches were

almost a daily occurrence, and despite a police station being set up in

the train station, heroin was still being sold openly only meters away.

One night in 1997 some person or persons unknown emptied a machine gun

into the doorway of a female aboriginal elder's house (the council of

elders opposed the relocation of the residents of The Block). The

newspapers (which were already publishing shock stories about the drugs

in Redfern) the next day ran a story about right wing extremists

terrorizing the Aboriginal population, although nobody was detained over

the attack and nobody saw who the attackers actually were.

The atmosphere in the area was degenerating into violence and

resentment. Nothing was being done to improve the living conditions of

Block residents and no policy of prevention or harm minimization was

attempted in regards to the flow of heroin into the suburb. A needle

exchange program consisted of simple handing out hundreds of syringes

each day without any support, counseling or care offered or available.

The local exchange program was halted after public outcry over a

newspaper photograph of a 15-year-old white boy injection himself with

heroin in an alleyway in Redfern. After this action a Commonwealth

Health Department car would simply leave 1000 syringes in the middle of

Everleigh Street every morning, not even bothering to pick up the used

syringes. The pressures upon the community seemed to be coming from the

very top levels of Australian society and Government. It was the final

stage in the "gentrification" of the inner city area of Sydney.

Most of the artist run spaces in Redfern had been evicted and

demolished by the end of 1997, and the process of "gentrification" was

well and truly underway. Throughout 1997-98 Redfern was the subject of

several shame articles in the tabloid press, and real life "shock TV"

programs. The traders of the Redfern Street clothing factory seconds

shops began to notice a drop in trade at this time and many were forced

to close by early 1999. Appeals by the local small business organization

to begin a plan to revitalize the area, using the vehicle of Aboriginal

culture as a means of achieving this were met with brush-offs and

silence from local and state politicians. Real estate speculation was

not suffering however, and the first million-dollar terrace house in

Redfern (Pitt Street) sold at auction in mid-1997. The cafe culture also

began to establish itself in Redfern and Regent Street, although they

did not yet open at night when the windows were covered with very heavy

security grates. I left Redfern on 21st February 1996 to help nurse my

grandmother through the last weeks of her life. Although I would live in

Redfern again the necessary lessons had already been learned.

I was fascinated by the stories and struggles of the Aboriginal

people and after a short time of living in Redfern I wanted to learn to

play their long flute-like instrument from the far north of Australia.

Most people call it a Didjeridu, but that is a European interpretation

of the name based on the sound the instrument makes. The Aboriginal

people call it by several names, some being Yiraka or Yidaki ( trachea),

Artawirr (hollow log), and Ngaribi (bamboo).

My first Didjeridu

was a copper pipe, played a bit like a trumpet, but with a small enough

aperture to make it easier to circular breath, as is needed to play

Didjeridu. Shortly after this a friend of mine who lived in an isolated

Aboriginal community in the far north of Australia sent me a Didjeridu.

This instrument I played for a year, until I had the opportunity to

leave Australia and travel as a near destitute backpacker. When I

arrived in England in 1997 an English friend gave me his Didjeridu as he

was about to go to Australia and could not carry the heavy instrument

with him. So I was now broke and in Europe with a Didjeridu. I began

playing on the streets as a busker, earning enough money to survive and

stayed in Europe for 18 months, meeting up again (we first met in India

in 1996) with the girl who I would eventually marry and set up a home

with.

I lived as a street musician in Amsterdam for most of

1998, and have played at cafes and festivals in Spain, Holland,

Germany, Sweden and Belgium. In Amsterdam I spent 3 days in the company

of Alan Dargin who was one of the two best Didge player I have ever seen

(the other is Charlie McMahon). My most recent achievement was playing

at the 397th and 399th Saami Winter Market in Jokkmokk in the far North

of Sweden, in February 2002 and 2004 where I was part of a group of

Saami, Inuit, Swedish, American, Japanese and British musicians whose

first performance (2002) was recorded by Finnish radio. The second

perfromance was the highlight of

a multimedia web project

undertaken by Umeå University.

Playing the Didjeridu has given me many opportunities to meet

people. There is much interest in the instrument and the ancient culture

it represents. The Didjeridu is more than just an instrument for me, as

it has a presence that is difficult to describe without using spiritual

terminology. The breathing technique and the hypnotic tones it produces

have a highly meditative effect on myself and often on those who

listen.

The Didjeridu has become identified with what is labelled

The New Age. I think of myself as coming from a culture which is

described in the book “The Didjeridu: From Arnhem Land to Internet” , as

alternative lifestylers’ whose “model society is based on four

essential elements; firstly holism of experience, secondly community

with it’s qualities of interrelatedness and co-operation, thirdly

ecology, with its sustainable ethos and fourthly, a creative spiritual

milieu.” (Neuenfeldt et.al. p140). It goes on to say that it is the

rejection of materialism by alternative lifestylers’ which separates us

from the New Age movement, which “has become in many cases a highly

commercialised and profit making industry” (ibid.).

Bibliography:

Neuenfeldt Karl (Ed.) The Didjeridu: From Arnhem Land to Internet John Libbey Publishers. Sydney. 1997

By james barrett